There are other patterns to practice besides major and minor. To better understand this, we need some music theory:

Modes

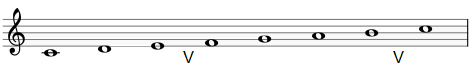

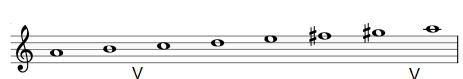

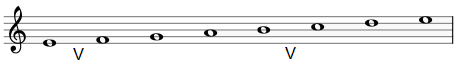

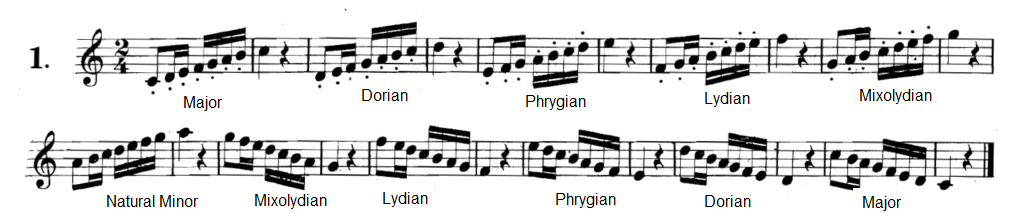

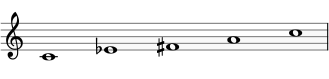

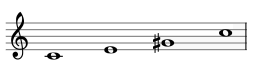

The location of half-steps and whole-steps change with the mode of the scale. For example, in C major, the half-steps fall between E-F and B-C:

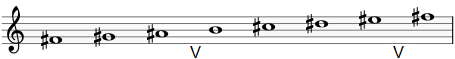

In major, the half-steps fall between the 3rd-4th scale degrees and the 7th-8th scale degrees regardless of the key. It is the location of the half-steps that makes it a major scale. And this is true for all major scales. For example, F# major:

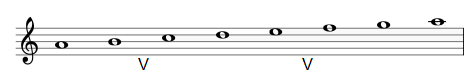

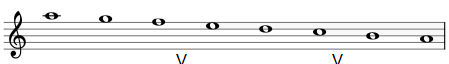

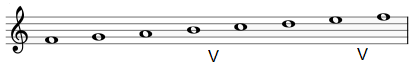

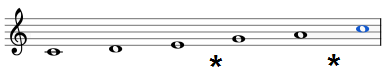

In natural minor, the half -steps are between 2-3 and 5-6:

There are two additional forms of

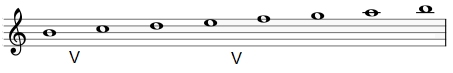

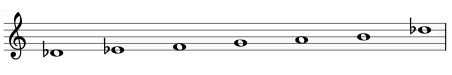

Major and minor are two of the modes; there are five others. Here are all the modes:

If you practice the Arban scales, you will see that he has you practice these modes as a part of the major scale study.

Arban did not include the

Pentatonic, Chromatic, Whole-Tone, Octatonic and Other Scales

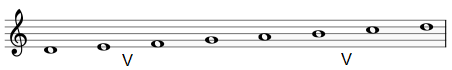

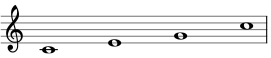

The pentatonic is a five-note scale pattern that can be built on 12 different starting pitches. Here is the version beginning on C:

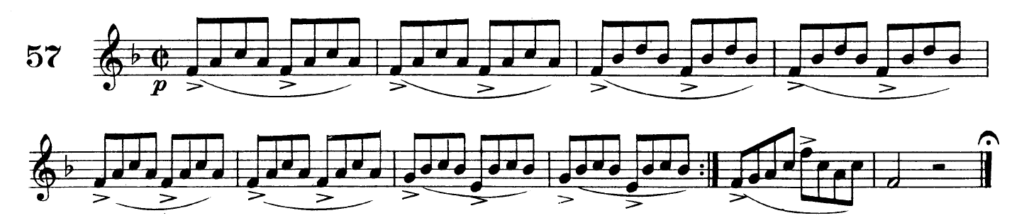

And, let’s not ignore the chromatic scale. Clarke’s First Study is great practice, as are the chromatic scales in the Arban Method.

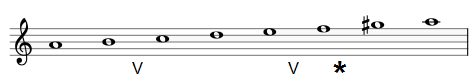

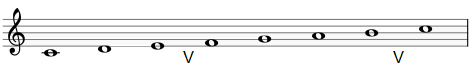

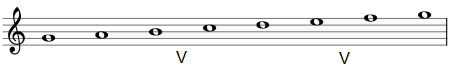

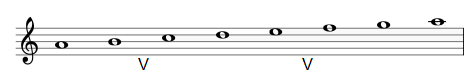

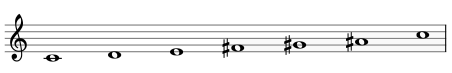

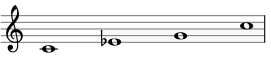

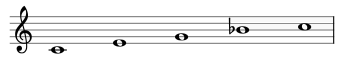

There are two whole-tone scales — they don’t show up often; if you practice them now, you won’t have any problems when you run across them in a piece of music:

You’ll notice that there are only six notes in these scales and there are no half-steps, only whole-steps. These scales became very popular in French music at the end of the 19th century with composers like Debussy and Ravel.

And there are more, like the octatonic scale These will not show up very often, usually in 20th-century music. There are a number of jazz scales, too. (Some of the modes are considered jazz scales.)

Remember this: the more scales you know, the less surprises you’ll encounter learning new music.

While You’re At It…Practice Chords, Too

Besides scales, you need to know chords, especially major, minor, and dominant seventh chords — in ALL keys! You should also learn the three fully diminished chords and the four augmented triads. This practice will cover the vast majority of

For practice material on chords, start with the Arban — it is truly an

There are COUNTLESS other books with scales and chords and you can make up your own patterns. It may be tempting to write your exercises down or put them in a music notation program to transpose them to all twelve keys, but you really are better off doing this in your head. It WILL make your brain hurt, but you will grow significantly in your abilities by doing this. Remember what weight lifters say: no pain, no gain. That’s just as true for mental growth.

I should add at this point that there are two requirements to

- You have to identify the scale or chord. (Studying music theory will make this much easier!) If you don’t or can’t identify the scale/chord, your mind can’t access the appropriate practice memories.

- You must have already practiced the scale or chord you identified. If you identify the scale/chord but haven’t practiced it, there are no practice memories for you to access. (

Piano practice of scales and chords is just as helpful as playing them on trumpet, particularly playing them from memory: you can see what you’re doing and it doesn’t make your lip hurt!)

I didn’t really understand what I’m telling you until 1995 (I was 34 years old and had been playing trumpet for 24 years) during a conversation with Michelle Kaminsky at the Moscow International Trumpet Competition. Michelle told me, “I agree with Rafael Mendez — if you know all your scales and chords, it shouldn’t take you long to learn the music.”

Brilliant! And so obvious that I never saw it. After all, what is a piece of music? It’s scales (or scale fragments) and chords combined with different rhythms.

Michelle had paid her dues — she told me that while she was at the University of Illinois she played the ENTIRE Clarke Technical Studies EVERY DAY for TWO YEARS! I asked her how long that took — she said about an hour to play all 49 pages because she didn’t take all the repeats.

She tied for first place at the Competition, but in my mind, she was clearly the best trumpeter there. The field of competition was STRONG, including Craig Morris who later played first trumpet in the Chicago Symphony for two years.

Michelle could play ANYTHING! Is it any wonder? After 730 hours of daily scale and chord practice??

Practice your scales and chords!! They’re good for you!!