You might notice I didn’t say “High” Range — I think a lot of people have a quite reasonable fear of heights, but I don’t think too many are afraid of “upper.” When I was in college, we stopped calling notes “high” — it was just “C,” not “high C.” It helped!

So, Thing to Practice to Improve Upper Range, in no particular order:

Lip Slurs, like the Colin Advance Lip Flexibilities

Range Expansion Slurs, which might be better called Tone Studies Expanding into the Upper Range

Shakes, i.e., lip trills, above the staff

Clarke Technical Studies No. 2, which only go to the top of the staff, so transpose what’s written up an octave to extend into the upper range

David Laubach told me to play a mid-range study, take it down an octave, and then take it up two octaves. Taking it down encourages relaxation and moving a lot of air, which helps in the upper register.

Clarke Technical Studies No. 5, as written — transpose into “higher” keys to go above F

Play high music, I mean, music in the upper register, either music written in the upper range or transpose that isn’t. When you can play a song with a good tone and endurance, raise the pitch a half-step. Repeat this process to increase your strength and range — it worked for Maynard!

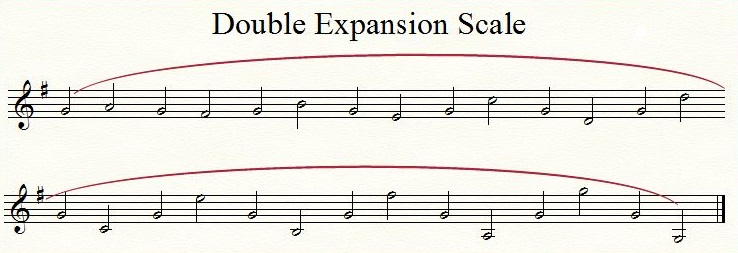

Double Expansion Scales, such as:

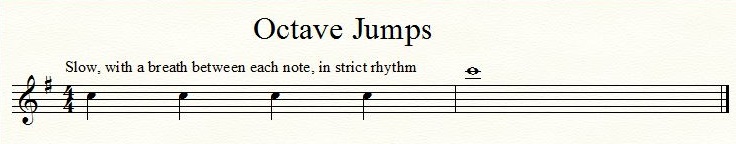

Octave Jumps — I don’t have a definite system for this, but often I’ll play something like:

The idea is to play the first four notes so you build confidence and a consistent approach. When it’s time for the octave, do everything exactly the same…except more of it. It’s like when you were a kid playing on a swing set: to go higher, you did the same thing as before, just more of it.

Mouthpiece Rim — Arnold Jacobs told me that the lip muscles need to increase in strength to play higher. In addition to practicing on the trumpet, he recommended practicing on a mouthpiece rim. Why a rim? Because it is difficult to buzz above “high” C on the mouthpiece unless you are extremely strong. A rim has no acoustical properties, so it is not difficult to buzz in the upper range. Here the rest:

Then [Mr. Jacobs] asked me what the highest note was that I could buzz on the mouthpiece. I don’t remember what I told him, but he told me to buzz that note and hold it for 6 seconds. After doing that, I was supposed to rest for a few moments and do it again, for a total of 6 repetitions. In time, my muscles would “hypertrophy.” (Remember, Jacobs studied medicine for a hobby. Most of us would say the muscles would “build.”) When that happened, I was to buzz a half-step higher, and so on. (from More Thoughts on High Range)

One more thing — one of the few things I remember from my high school biology class was something the teacher said in passing: “Use it or lose it.” For most of us, this is true, although a few, rare individuals naturally possess great strength in their facial muscles. If you’re like me, if you want to increase your range, you have to keep at it. It takes time to add range, frequently a month or two, so persistence and patience need to be added to the list of things to practice!

If you’re wondering why it takes so long to build upper range, consider this — Arnold Jacobs stated that each time you go up an octave, everything doubles, including the strength to play. Using “pretend” numbers, here’s what we get:

Low C = 10, Tuning C = 20, “High” C = 40, Double C = 80

We’re going to pretend that adding a half-step requires 10% more strength, so raise these C’s to C-sharps, we need:

Low C# = 10+1, Tuning C# = 20+2, “High” C# = 40+4, Double C# = 80+8

You can see that you only need to increase by 1 to go from C to low C#, but three octaves higher, you have to increase by 8. And, until you increase by 8, you can’t play any higher…how do you play 1/8 of a step above double C? The trumpet won’t do it, so you are stronger but it doesn’t help your playing until you reach the full 8. Clear as mud? I hope not!